On Novel Grounds, Philadelphia Judge Rejects Uber’s Bid to Arbitrate Passenger’s Personal Injury Claim

By Charles B. Casper and Robert E. Day

If your company uses an online agreement and sells to Philadelphia residents, you will want to know about a January 3, 2020 Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas ruling in Kemenosh v. Uber Technologies, Inc. The court refused to enforce the arbitration agreement in Uber’s Terms of Service on grounds contrary to settled law.

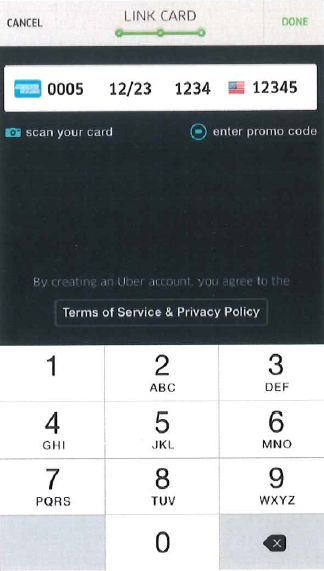

Uber’s sign-up screen notified customers that “By creating an Uber account, you agree to the Terms of Service & Privacy Policy.” Those terms were accessible by clicking a hyperlink embedded in the phrase, “Terms of Service & Privacy Policy.” But Judge Abbe Fletman concluded that those words convey only “that by creating an Uber account one is agreeing to pay money in exchange for transportation, and to the terms of a privacy policy. They do not convey an offer to arbitrate, or notify the user in any way that the offered Terms of Service contain a waiver of jury trial and an arbitration clause.” Through this sign-up screen, “Uber has proven only that there was a meeting of the minds on an agreement … to pay money in exchange for transportation,” not to arbitrate disputes. She denied Uber’s motion to compel arbitration on this basis.

Courts have long required online sellers to give customers reasonable, or in some jurisdictions conspicuous, notice that by proceeding to create an account or buy something they are agreeing to a contract, and to make the contract readily available in a scroll-box or by clicking an easy-to-see link. “Browsewrap” agreements like Uber’s allow a consumer to accept a contract without being forced to scroll through the full agreement in a window or click a link and read it. Meyer v. Uber Techs., Inc., 868 F.3d 66, 75 (2d Cir. 2017). Courts enforce these contracts so long as the company’s offer provides sufficient notice that the contract exists, if it is readily accessible. See, e.g., id. at 76; Fteja v. Facebook, Inc., 841 F. Supp. 2d 829, 834-41 (S.D.N.Y. 2012). But courts do not require sellers to disclose the numerous terms and topics the contracts include—here, arbitration—on the sign-up screen. Instead, as the Pennsylvania Superior Court (Pennsylvania’s intermediate appellate court) has held for printed contracts, “the failure to read a contract before signing it is an unavailing excuse or defense and cannot justify an avoidance, modification or nullification of the contract … Accordingly, the consequences of any failure to actually read the document … prior to signing must be borne by the [customer].” Fellerman v. PECO Energy Co., 159 A.3d 22, 27 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2017).

The Philadelphia court departed from this settled law by analyzing whether Uber’s on-screen offer conveyed to a customer who chose not to read the contract that it covered arbitration as well as transportation. Must the on-screen offer also convey that it covers disclaimers of liability for some claims? Or limitations on remedies? Or requirements that suits be filed in only in the company’s home state? The list of required topics could be far too long for the on-screen space.

When courts decline to enforce these agreements, it is not because the on-screen offer did not include the topics the contract covers, but because it was not presented in a way that reasonably informed the customer that the agreement exists, and that continuing with setting up an account or making a purchase constitutes assent to its terms. See, e.g., Wilson v. Huuuge, Inc., 944 F.3d 1212 (9th Cir. 2019); Cullinane v. Uber Techs., Inc., 893 F.3d 53, 61–64 (1st Cir. 2018); Nicosia v. Amazon.com, 834 F.3d 220, 235–38 (2d Cir. 2016); Sgouros v. TransUnion Corp., 817 F.3d 1029, 1034–36 (7th Cir. 2016); Nguyen v. Barnes & Noble Inc., 763 F.3d 1171, 1175–79 (9th Cir. 2014).

The closest analogy that comes to mind to the Philadelphia court’s view that the company must tell the customer about arbitration in its offer is the Ninth Circuit’s view in Norcia v. Samsung Telecommunications Am., LLC, 845 F.3d 1279 (9th Cir. 2017). There, the court reasoned that “a warranty generally does not impose any independent obligation on the buyer outside of the context of the seller’s promises,” so notice that a warranty covered a product did not, without more, convey that the customer was agreeing to anything else, including arbitration. Id. at 1288. Here, Judge Fletman observed that “[i]t is generally understood that Uber offers transportation in exchange for money,” so notice of “Terms of Service” did not convey that the agreement might cover anything else, like arbitration. But online contracts for goods and services commonly cover other topics—such as where a suit can be brought, limitations on liability or remedies, or arbitration. Consumers are well aware of this, which is why courts require companies to call a contract’s existence, not its topics, to the consumer’s attention.

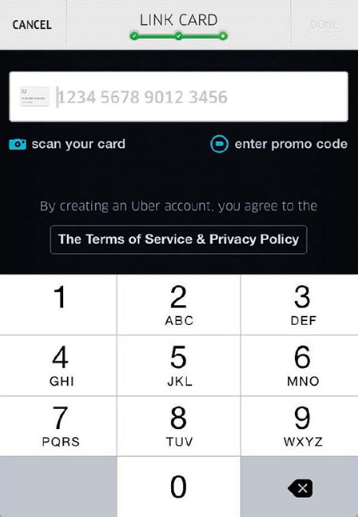

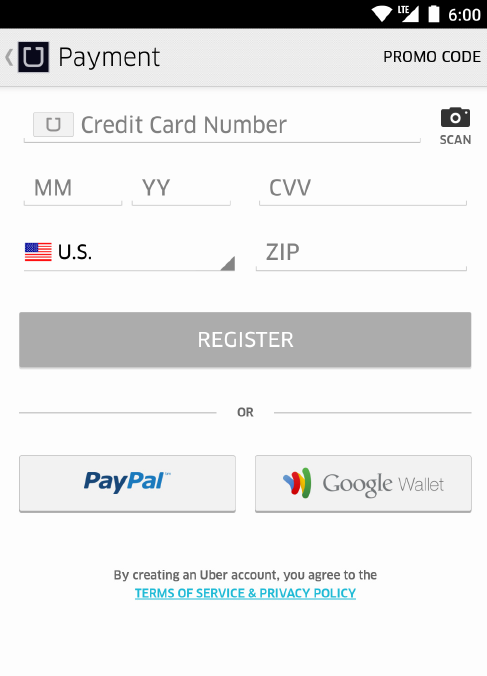

Whether Uber’s sign-up screen sufficiently called the contract’s existence to a customer’s attention is a fair question. The First Circuit held that it did not, due to perceived defects in its design, including the screen’s title, the unusual appearance of the link to the contract, and the number of similar looking items on the screen competing for attention. Cullinane, 893 F.3d at 63–64. On the other hand, the Second Circuit enforced the contract resulting from a similar Uber screen in Meyer, 868 F.3d at 77–80. See Fig. 1 [screen here]; Fig. 2 [Cullinane screen, same as here]; Fig. 3 [Meyer screen]. Neither Court of Appeals required the sign-up page to tell consumers that the contract included arbitration or any other particular topic.

The Philadelphia court’s opinion seems to acknowledge that reasonable notice of the contract’s existence and easy access to its terms are the issues for enforceability. The court detailed the screen’s problems as in Cullinane, and suggested that Uber could have done things differently that might have led to enforceability:

- Require customers to click the link and scroll through the contract;

- Check a box certifying that she had read and agreed to the contract and privacy policy;

- Make the link to the contract a conventional hyperlink in underlined blue type;

- Advise customers that they should read the contract; or

- Tell customers the contract contained further essential terms.

All but the last of these factors go to whether the contract’s existence, not its topics, were properly disclosed. See Cullinane, 893 F.3d at 63–64. Yet the court nonetheless premised its decision on the lack of “an offer to arbitrate.”

Uber has a right to appeal the Philadelphia court’s decision to the Pennsylvania Superior Court. If it does, the Pennsylvania appellate courts will have an opportunity to consider assent to online contracts for the first time and to bring the analysis of Uber’s screen into line with well-established precedent. In the meantime, the Philadelphia court’s decision does not bind other judges in Philadelphia or elsewhere in Pennsylvania.

Fig. 1 (Kemenosh)

Fig. 2 (Cullinane)

Fig. 3 (Meyer)

Fig. 3 (Meyer)